28 October 2025

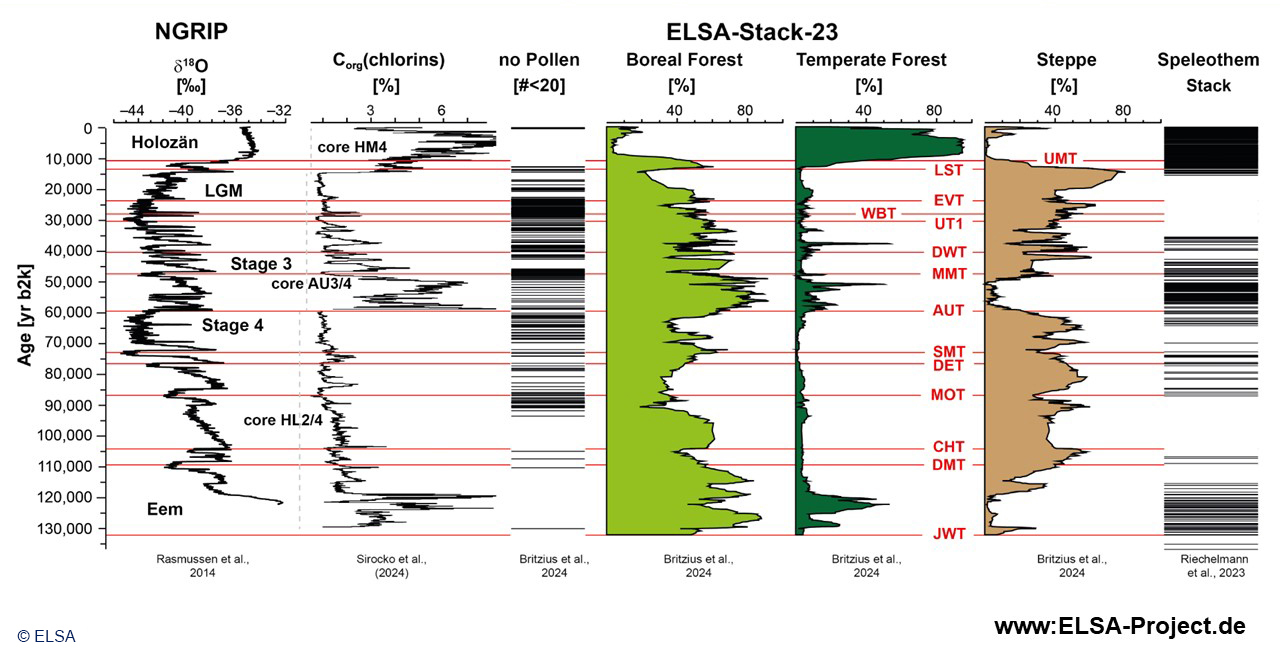

The collection of samples in the ELSA geoarchive provides a unique record of the climate of Central Europe over the past 130,000 years. The archive provides insights relevant to many research fields and disciplines. Over the last 25 years, the Eifel Laminated Sediment Archive has supplied data for three books, some 50 student theses and doctoral dissertations, and at least 60 research papers. And there is still an extensive range of fascinating open questions. Thus, it is essential that drilling continues, even though Professor Frank Sirocko, who spent many years building and expanding the ELSA geoarchive, will soon be taking his well-earned retirement.

The sediment cores in the Eifel Laminated Sediment Archive (ELSA) are in some cases more than 100,000 years old – and still they are full of life. "However, some research data that these cores provide have to be taken in the initial six weeks after the core has been extracted because the organic substances of the lake deposits oxidize rapidly, which alters the corresponding biomarkers," explains Professor Frank Sirocko. The drilling projects in the maars of the Eifel region will thus be continuing after his retirement. As a result, the ELSA geoarchive of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) will continue to grow and invite researchers to examine the cores with ever-new analytical methods, such as for the investigation of ancient DNA.

ELSA is a remarkable archive of core samples that hold answers to many research questions. It was initiated when Frank Sirocko was appointed Professor of Geoscience at JGU back in 1998. Over the years, Sirocko has put together a repository totaling some 2,700 meters of core samples that today are stored in the basement of the building of the Faculty of Natural Sciences under optimal conditions. The temperature of 8 degrees Celsius and the 70 percent humidity they are exposed to ensure that they degrade as slowly as possible.

About two years ago, Frank Sirocko turned from a full professorship at JGU to a senior research professorship at the Institute of Geosciences. He continues to contribute his expertise to various research projects and is closely collaborating in particular with Junior Professor Igor Obreht, who is also a specialist in the field of paleoclimate research. In this, Sirocko is eager to also share the very practical experience of more than 25 years of being involved in various core drilling projects. "My work for ELSA has given me a whole lot of respect for the inhabitants of the Eifel region," he emphasizes. "As you can imagine, locals do not tend to welcome you with open arms when you come along for the purpose of conducting a research project on their property. But when you have a well-defined plan and negotiate on equal terms with the farmers there, they provide you with the very best of support."

It is with a smile that Sirocko remembers the early days of the project. No more than a handshake was necessary back then to settle the question of the provision of financial compensation should the drilling work result in damage to a farmer's agricultural land. "In this part of the world, face-to-face agreements counted for far more than any official authorization documentation could. The growing basis of trust provided the groundwork that enabled us to identify the most promising sites for drilling."

A new research field in the Eifel region

Sirocko studied marine geology at Kiel University in northern Germany, where he also obtained his doctorate, before relocating to Columbia University in New York. He returned to Kiel to acquire his postdoctoral qualification before undertaking research in Cambridge and Potsdam. Finally, a Heisenberg fellowship from the German Research Foundation (DFG) paved the way for his appointment as a full professor at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

Here awaited him a challenge that he turned into his advantage. He submitted a successful proposal for funding to the Rhineland-Palatinate Trust for Innovation and was rewarded with a budget of then DM 500,000. "That allowed us to drill when and how we needed to carry out our research. The freedom and flexibility when it came to project design were extremely valuable and even today represent the bedrock of the remarkable achievements of the ELSA project."

But why exactly did Sirocko choose the Eifel region for his research? "Well, it was a quite simple decision as this area that has been shaped by volcanic activity has preserved a geological archive that is second to none," Sirocko points out. During the most recent ice ages, the Eifel was not covered by glaciers so that fine layers of sediments were deposited without interruption for tens of thousands of years. They formed annual layers known as varves that are comparable with the annual rings in tree trunks. These sediments are present in the maars that are characteristic of the region. The maars were originally volcanic craters. Some of them are today dry maars that have been filled in while others are lakes containing water. For the purpose of obtaining cores for ELSA, the researchers used various techniques to drill on dry land as well as down from the water surface.

Sirocko and his team managed to complete the first 20 drilling projects in just two years. "All at once, we did have a wide selection of good quality cores. Thus, we were quickly able to undertake comparative analyses, identify certain patterns, and target future drilling activities," recalls Sirocko. It soon became apparent that the core sample inventory came with two major benefits. Firstly, each of the fine layers of laminated sediments could be practically assigned to individual years, providing a detailed chronology reaching back more than 100,000 years. However, it would take decades of careful detective work on the overlapping core samples to determine the uninterrupted time sequence of the individual layers that would make up a full-scale chronology.

The second benefit of the long-term project showed when the team discovered very early on that the core samples could not only be used to reconstruct climate history and climate development over thousands of years but that the samples also stored much more information that was relevant for many other fields and disciplines. "Say you want to know more about volcanism 74,000 years ago, all you have to do is look at the ELSA data. You will then know if this was a period of active volcanism and where to find the best cores covering the years in question."

From archaeology to paleogenetics – in the Eifel and beyond

Of course, Professor Frank Sirocko and his team used their insights from researching the drilling cores to deduce details about volcanic activity in the Eifel region. "We were able to date the eruptions in the Eifel in the previous 130,000 years and correlate them with changes in the Atlantic Gulf Stream. It became clear that there was a link between the lithostatic pressures of the continents and ocean. Volcanic eruptions always occurred more frequently when the ice age glaciers melted, warming the North Atlantic. We published these findings in 2024, and they were highly appraised by the research community," Sirocko remembers.

With the help of the sediment cores, it is also possible to obtain important information on the history of human settlement and the development of agriculture. "There are lots of overlaps with the fields of archeology and anthropology that facilitate the understanding of human settlement in the Eifel region in detail and in the whole of Central Europe in general." One major source of information in future will be the analysis of DNA traces in the sediment cores. The study of fragments of preserved genetic material that are thousands of years old will, for instance, enable paleogenetic researchers to determine what plant species were used as crops in the past, what animals had their habitats in the catchment areas of the maars, and when humans first arrived in the region.

"In winter seasons with cold period conditions, we should be able to trace the migration of mammoths and of mammoth hunters," says Sirocko, citing a typical example. And there is one aspect that particularly interests him: "What effect did climatic tipping points have in the context of human settlement?" At the same time, Professor Frank Sirocko is not just concerned with events relating to climatic changes but also with topics such as historical epidemiology. "The oldest evidence we have for plague dates to 3,200 BCE. This remarkably corresponds with a phase in which the markers for settlement disappear in our sediment cores for around 100 years." Based on this finding, the ELSA team plans to search for traces of the DNA of plague bacteria dating to this time. "Ten years ago, we were already able to do this for the Black Death around 1348," says Sirocko.

Home advantage for geoscientific research at JGU

Frank Sirocko has a clear vision for the future. He would like the Eifel to remain the 'hotbed' for the geosciences in Mainz in view of the multiple insights and perspectives made feasible by the drilling samples obtained from the region. He is looking forward to continue working together in drilling and research projects with Junior Professor Igor Obreht, whose biomarker expertise will provide important new stimuli, particularly in connection with molecular analysis. Additionally important for the ELSA pioneer is the interdisciplinary approach: "Having access to traces of ancient DNA is a dream for paleoecologists," says Sirocko. "However, it is also a massive challenge for computer scientists who have to cope with terabytes of sequence data."

Sirocko will certainly remain busy until his senior research professorship ends in late September 2026. There are findings that have yet to be put down on paper, and new sediment cores are waiting to help answer new research questions – in the geosciences, in climate research, in paleogenetics, and in many other fields of research.