1 December 2015

The Clemens Brentano Collection provides intimate insights into the life and world of one of the greatest German Romantic poets. Along with hundreds of examples of lively correspondence, there are drafts of poems and household plans, outlines for dramas and drawings. The collection, which was acquired by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) in 1950, is housed in the Mainz City Library.

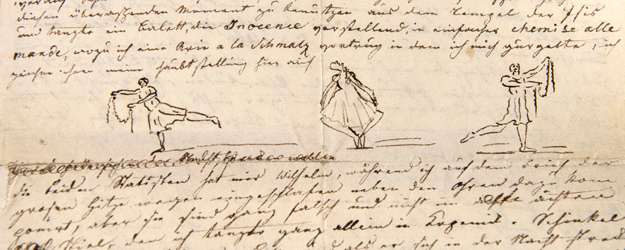

Clemens Brentano must have kept this night in memory for a long time. The bed was wuite uncomfortable and his legs became numb. There is a sketch that shows the poet on the bedstead. He wrote to Susanne Schinkel about his experience: "When I couldn’t feel my legs in the morning, I finally found them because a mouse bit me on the heel." Brentano, clothed only in a "chemise allemande" nightshirt, sprang out of the bed and commenced a furious dance on the floor. "Here are illustrations of my main positions," he added. There follows a series of cartoon-like pictures in which the poet pokes fun at himself.

"This really doesn’t fit with our customary image of the sober and serious Brentano," says Karen Stuckert, who has just removed the letter from a white envelope of acid-free paper and has carefully opened it. Although the document from the year 1811 shows traces of the passage of time, it still appears to be in good condition. This autograph letter is part of the Clemens Brentano Collection, which is the property of the University Library of Mainz University but which was given to the Mainz City Library on permanent loan together with all the manuscripts and other hand-written materials in 1997.

Six hermetically protected archival document boxes

"We are happy to provide support for the collection with our expertise on old things," explains Dr. Annelen Ottermann, Deputy Head of the Mainz City Library and head of its department responsible for manuscripts, old prints, and the conservation of the library’s holdings. "And we gladly accept this support, particularly in view of the fact that our university library on campus is primarily a library for users," adds Stuckert, who is responsible for the collection on behalf of the Mainz University Library.

The entire autograph collection is stored in six archival document boxes. They stand on two shelves in a narrow but endlessly long, hermetically-sealed room in the city library. They are stored with special collections and manuscripts that are up to 1,000 years old. "Don’t be misled by the seemingly small number of boxes," warns Ottermann. "A lot can fit in such a container." She picks one up and takes it into the reading room in order reveal the treasures it contains.

Essentially, the fact that the collection is here is testimony to a failure. The Aschaffenburg wholesaler Franz Johann Dessauer wanted to found a Brentano museum in his home city. So from 1928 and with the help of the publisher Paul Pattloch, he began to collect manuscripts relating to the poet and managed to add letters written to Brentano to his collection. Most of these came from the estate of his sister Bettina von Arnim, which came up for auction in Berlin in 1929. But there are also many handwritten documents by Brentano himself – such as the letter which he wrote to Susanne Schinkel, the wife of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, one of the most prominent master builders and architects of German Classicism.

Poems, drawings, and scribblings

The Second World War brought the dream of a museum to an end. The Brentano house in Aschaffenburg, in which the poet died in 1842, was destroyed in 1945. However, the collection survived in the safes of the Pattloch bookstore. "It was bought by a doctor in Saarbrücken before it came into the possession of Mainz University," reports Stuckert. The re-opening of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in May 1946 brought with it various donations and targeted purchases designed to promote the establishment the young university. "Aschaffenburg was within the archbishopric of Mainz and was thus part of the electorate," explains Ottermann. "This connection probably played a role in the decision to purchase."

Hundreds of documents have survived. A few of these are now spread out on the table in the reading room. "I find it interesting that people at that time used these pieces of paper for everything possible," says Stuckert, picking out a large folded piece of paper.

On it are various drafts of poems written by Brentano himself. He has crossed through quite a number of passages. Anyone unfamiliar with Brentano's handwriting would find it very difficult to read the text. Even Ottermann, who is routinely exposed to it, has problems here and there. "With God ...," she reads haltingly, having to look twice.

However, clearly recognizable are the scribblings between the stanzas. It looks as if the poet, pausing and lost in thought, simply drew a few lines on the sheet. There is also a pencil drawing of a woman wearing a headdress. And Stuckert turns the sheet over to disclose the beginning of a play. The words "First Act" are easy to read. Then it becomes difficult again.

Grasping the Brentano letters

There is a lot of research to be done here and the collection is viewed repeatedly. "It's not as if we have to cope with massive numbers of researchers but the occasional person does find their way here," says Ottermann. "It's simply a unique experience to actually touch such documents. We as human beings rely heavily on our senses and everything we can literally grasp, sticks in our mind."

And the collection offers a lot to be discovered, such as Brentano's letter to Rahel Varnhagen, whose Berlin salon was an important location around 1800. The fine handmade paper has a watermark, which the poet has neatly left free. This time his writing is decidedly easier to decipher: "Why aren’t you writing, dear Rahel? Are you ill? Your letter to me was so hastily done and so interrupted with complaints about sickness ... " And there is even a fan letter from Brentano to Ludwig van Beethoven. It begins "My very dearest Beethoven! Through certain expressions of your art you have become such a lively and eternal consolation to me ... "

"In February 2015 our collection was fully digitized," points out Stuckert. Now anyone can see what treasures it contains with the help of the online Visual Collections website of the Mainz University Library or the Kalliope Union Catalog. Nevertheless, a visit to the Mainz City Library is worthwhile. Getting to look at such a letter in the reading room, seeing the grease spots or the fine tears, the energetically crossed-out word or the self-portrait of the poet in a German nightshirt, is an entirely different experience to seeing these things online.