13 May 2015

Last year, the Goethe Institute awarded its German-Arabic Translation Prize in the Young Translators category to Mahmoud Hassanein, a doctoral candidate at the Faculty of Translation Studies, Linguistics, and Cultural Studies of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) in Germersheim. Here he talks about his work, about literature, and about cultures.

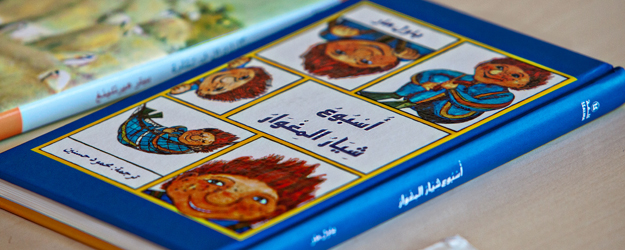

Almost every child in Germany knows the book "Eine Woche voller Samstage," which has become a modern classic among children's literature in German. Although the book has been published in English under the title "A Week Full of Saturdays," a more literal translation would be "A Week of Sams' Days." The Sams, the cheeky, freckled, red-headed, pig-nosed, wish-granting creature that sprang from author Paul Maar's imagination, grins broadly and brazenly from the blue book cover. But this particular version is rather different: Arabic lettering wanders across the pages and around the illustrations. The story seems to start from the wrong end, from the back of the book – in the same way as a Japanese manga comic. The strange and the familiar seem to have joined hands.

"Translating the Sams book – how do I go about this?," Mahmoud Hassanein asked himself about five years ago. "I approach each book differently," he explains, "I need a new strategy each time." Maar's book is filled with puns, rhymes, and the Sams or Slurb himself. "There is no point in simply being superficial in your approach." A translation word by word would completely sabotage the real meaning of the book.

No Thor thundering on Thursdays

"The Arabic words for the days of the week are simply derived from the sequence in which they occur. The Arabic week begins on Sunday, so the Arabic for 'Sunday' translates as the 'first day'; then there are the 'second day' and the 'third day' and so on.... In Arabic, we do not have a Thursday where Thor thunders and a Sunday where the sun shines, and anyway the sun shining would be nothing special for a child in the Arabic world. The sun is almost always shining there." So Saturday – or Sam's day – would simply be the 'seventh day,' meaning that the play on words would be lost. "I thought long and hard about the problem and did some research, and I indeed found older names for the days of the week in Arabic, antiquated names that are no longer used but which still have their own meanings," says Hassanein.

Hassanein is sitting in a small office in the German / Intercultural German Studies section of the Faculty of Translation Studies, Linguistics, and Cultural Studies of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germersheim. Momentary quiet seems to have descended in the room, which is just well as Hassanein is a very soft-spoken man. He even has a quiet smile when he talks.

Hassanein has been working as a translator since 2004 and has been a research associate at Germersheim since 2013. He is in the middle of his doctorate right now. The working title of his dissertation is "Human Rights and Translation." In November 2014, he was awarded the Goethe Institute's German-Arabic Translation Prize in the Young Translator category in Cairo, an honor that means a lot to him. "The prize represents a very real acknowledgment and confirmation of the value of what I do," says Hassanein proudly. There were famous names among the jury. "They were some of the foremost Arabic to German and German to Arabic translators."

Mulling over translation

Hassanein received the prize during a ceremony hosted by the Goethe Institute in the Egyptian capital of Cairo, the city where he was born in 1982. Here he studied German and Arabic at university. "I knew I wanted to study languages." But why did he choose German? "The first impression of a language is often the most important as is the contact with people who speak it." In Hassanein's case it was the German and Austrian tourists he met. It was this coming together that made up his mind for him. "To this day, I prefer the sound of German to that of French, for example." In addition, Egyptians tend to be fairly familiar with German-language literature. "Anybody interested in literature knows about Goethe and Schiller, but also Frisch and Dürrenmatt."

After graduation, Hassanein translated instruction manuals for cars and for a wide range of household appliances. He learned a lot, particularly about organizing his work as a translator. "After a while I had done everything that was possible for the company employing me." He wanted a new challenge. "I was still young – and had never been to Germany." He wanted to continue his studies. "So I came to Germersheim. It was here that I learned literary translation and how to mull over the best way of approaching it."

Mustafa Al-Slaiman, then a lecturer in Germersheim, placed a slender book in front of him and said: "You absolutely have to translate this." And so Peter Härtling's "That was Hirbel" eventually appeared in Arabic. It was thus that Hassanein's affinity with children's and young people's literature began, although he does not restrict himself to this genre. "I want to be as comprehensive as possible and try out different types of texts," he says. The recent prize was awarded to him for his translation of an excerpt of Wolfgang Herrndorf's novel "Sand" and Hassanein also wants to work on lyric poetry in the future.

Culture as construct

However, what he can best talk about at present is his experience of translating literature written for children and young people. His translation of Maar's "Sams" book proved popular with Arabic-speaking children in a Berlin kindergarten, he adds. "Even Paul Maar liked it." Maar himself also works as a translator, but he does not know Arabic. "However, I wrote an essay explaining my approach," explains Hassanein. He entitled it: "The Sams learns Arabic."

"Children's literature is not taken very seriously in Egypt," points out Hassanein. "Its importance is simply not recognized. There are popular writers who produce books for children but they are not really perceived as literary authors." A major project sponsored by the Ministry of Culture of Abu Dhabi helped him carry out the translation. "The project is designed to promote the translation of works from various languages into Arabic."

When asked about the cultural differences that might make it difficult for Arabic readers to fully appreciate the adventures of the Sams, Hassanein frowns slightly. "About the different cultures – I am not sure it is as easy as that. Whenever people talk about Islamic culture, they always seem to automatically equate the term with all of the Arabic world. However, a country like Indonesia is not Arabic at all. We all tend to put labels on cultures. This may make things easier but fails to account for their complexity. Cultures are constructs. It is people who make borders, who actively differentiate themselves from others and set themselves apart – these boundaries are not preordained. Actually, our cultures have a lot in common. There are Islamic fundamentalists as well as Christian fundamentalists. So there are similar viewpoints."

Krabat, Potter, and the Sams

Hassanein’s point of view is much broader. "In fact, you can actually talk of a childhood culture, one which is the same all around the world. Everyone knows Harry Potter and Harry Potter is Harry Potter wherever he pops up. It’s not important where he comes from."

It sounds like the Sams or Slurb might have a bright future. He grins just as broadly on the cover of the Arabic book that Hassanein brought with him. He has also added other works to his output of translations: Ottfried Preußler's "Krabat" is among them along with a dual language picture book containing an Arabic and a German fairy tale. Hassanein still has a lot to say – also about his doctorate on the Arabic versions of human rights declarations. But those are stories for another day. And so – for the moment anyway – this tale is told.