23 February 2024

Gemstones are fascinating wonders of nature, surrounded by a mystical aura of luxury. Dr. Tobias Häger is working on diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds every day. He is head of the Gem Materials Research group at the Institute of Geosciences at Mainz University, the only university-based team working in gemstone analysis in Germany and one of very few university institutions worldwide that is active in this specialized field.

The value of individual gemstones is difficult to measure because their appearances can be deceptive. The market price of a stone may depends on several factors, but color – which can be deliberately manipulated – is one of the most important ones. Therefore, gemstone materials research often involves the question of money. And sometimes this can be a great deal of money, says Dr. Tobias Häger.

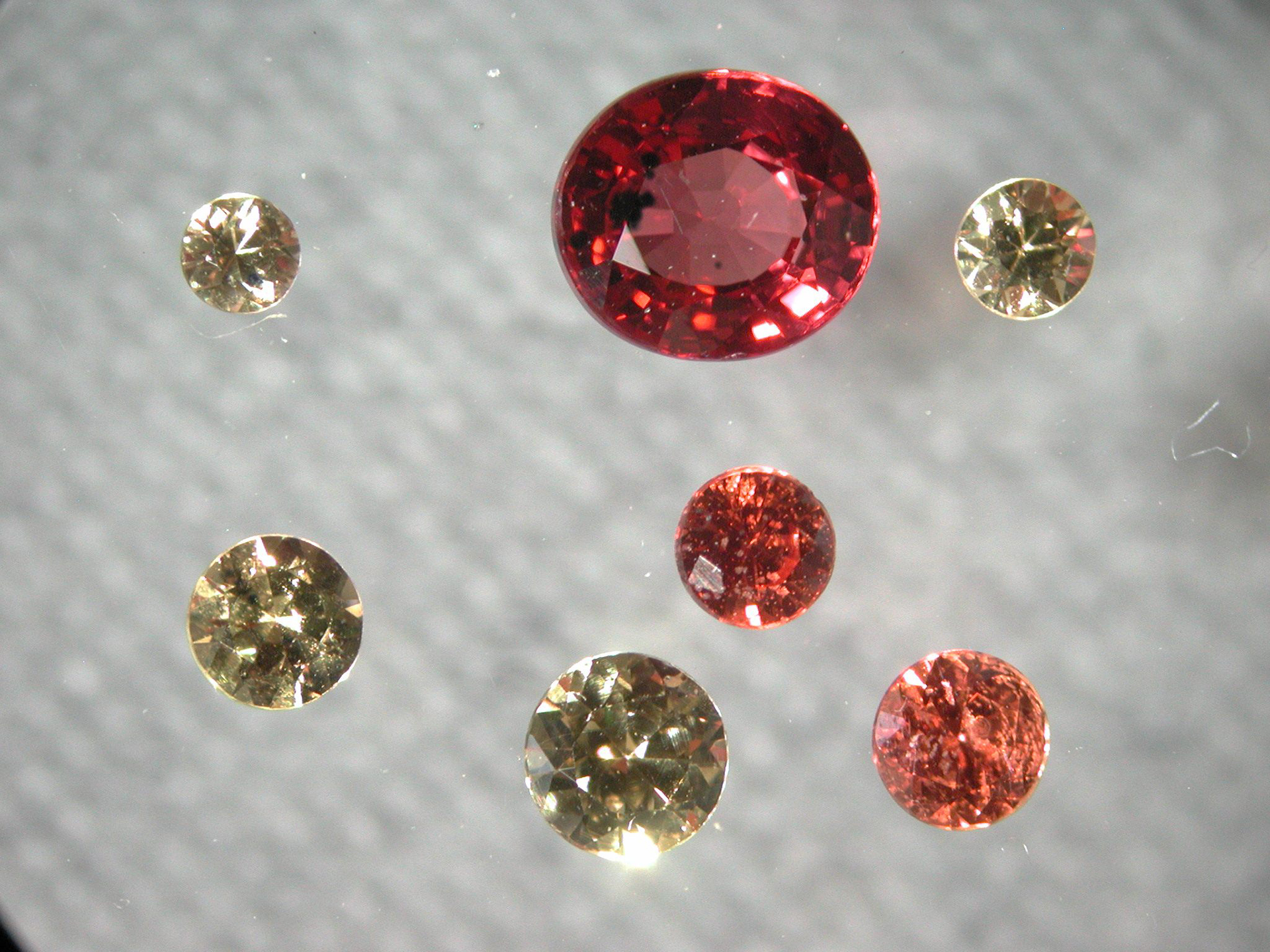

The Mainz-based mineralogist remembers one event in particular. In the early 2000s, an unusual number of yellow sapphires and orange corundum stones, also known as padparadschas, appeared on the market. The latter are among the most expensive colored gemstones. "Everybody wondered where they came from and why they were offered at comparatively low prices," he recalls. He was one of the researchers who investigated the matter in various international expert groups. They were able to prove that the color of the gemstones was not of natural origin and could not be attributed to the usual form of exposure to high temperatures either.

"A new method was being employed, a so-called beryllium diffusion treatment," explains Häger. At a temperature of around 1,800 degrees Celsius, sapphires react with added chrysoberyl powder (BeAl2O4). As a result, colorless sapphires develop an intensive yellow color and pink corundum stones turn orange. The sellers from Thailand had failed to disclose this treatment when selling the gemstones. "There were claims for indemnification worth many millions of US dollars," recollects Häger. "Colleagues of mine received even death threats intended to make them change their minds." Häger was not personally affected at the time. "But I did end up learning an awful lot."

The Idar-Oberstein outpost

Häger's work is not always that much of an explosive headline, but his research is fascinating in many ways. He heads the Geomaterial and Gemstone Research group at the Institute of Geosciences at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). The group's main scientific objective is to gather data on the formation and properties of gemstone materials. The Institute of Gemstone Research in Idar-Oberstein (IfE) is an external branch incorporated in JGU back in 1963. Thanks to this collaboration between Mainz and Idar-Oberstein, the European center of the colored gemstone trade, JGU is the only German university involved in gemstone materials research.

"What we do is purely scientific," Häger emphasizes. "We don't issue certificates. We focus on fundamental research." He himself is particularly interested in mineralogy, petrology, and the geology of deposits as well as in the field known as provenance analysis. Put simply, this involves determining the original location of a gemstone by looking at the characteristics typical of the original deposits. Thus, it is important that newly discovered sources of gemstones are scientifically documented – which is one of the responsibilities of Häger's team. The features of a new emerald site in Pakistan, for example, have been described recently in a doctoral thesis supervised at Mainz. This includes the analysis of major, minor, and trace elements in the stones as well as of any inclusions and the source deposit they come from. With the help of these attributes, it is possible to differentiate these emeralds from those found elsewhere, ensuring that the stones can be clearly assigned to their source. The results also help when it comes to the search for new gemstone deposits.

Inclusions and what they reveal

The necessary analysis procedures are carried out in the laboratory in Mainz. However, when convenient, the researchers sometimes travel to a gemstone site to obtain insights into the nature of the deposits there. In 2022, for instance, Häger and his colleague Elena Sorokina were in Greenland, which – as far as we know at present – is home to the oldest rubies in the world, formed a good two and half billion years ago. "We looked at the geology, petrology, and mineralogy in the area and were even allowed to take samples in the mine," points out Häger.

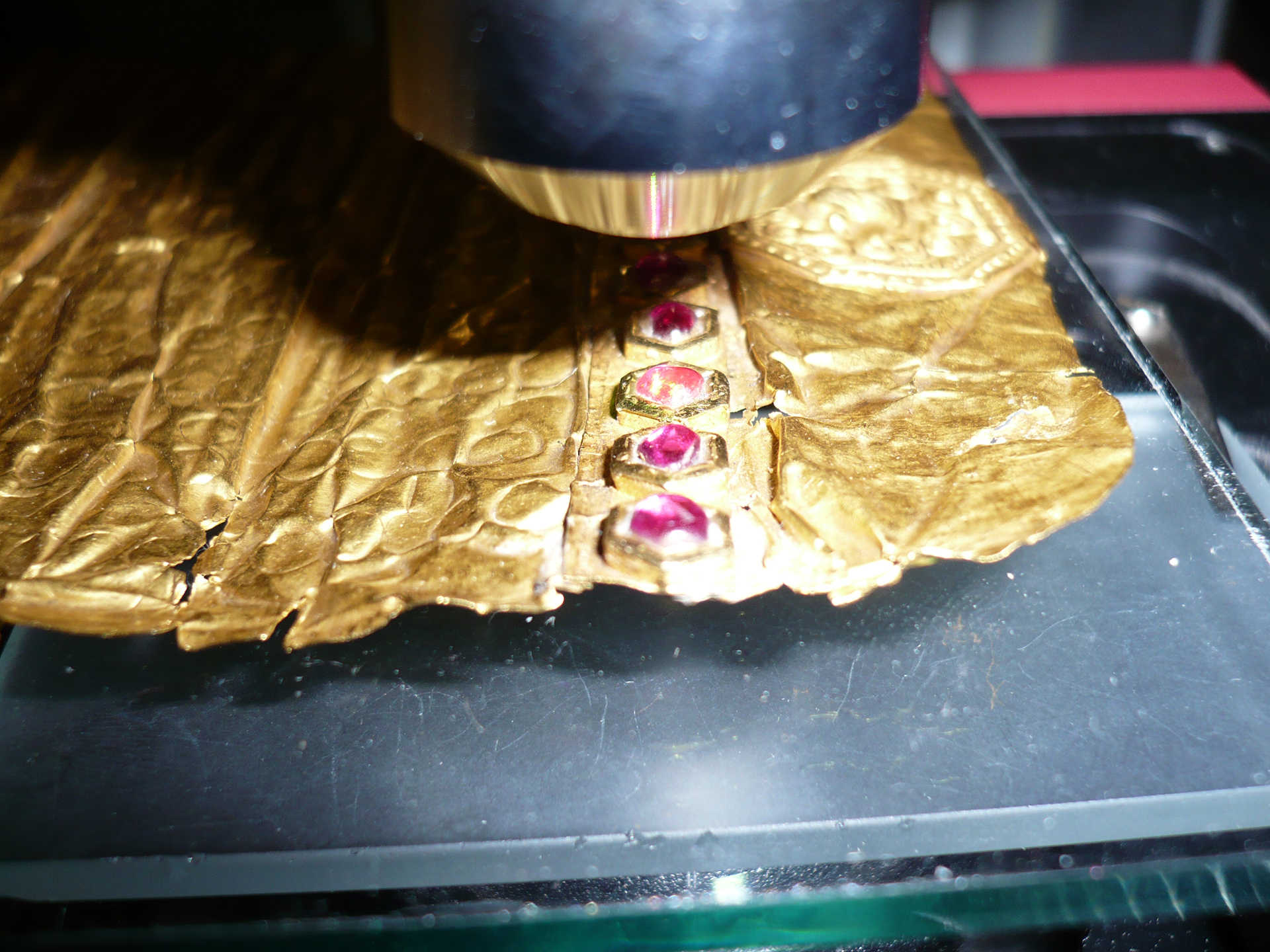

The researchers are particularly interested in the mineral inclusions within the gemstones, specifically the so-called syngenetic inclusions that were trapped inside the rubies when they were generated. These allow us to date a stone and, where a stone's origin is unclear, to assign it to a geographic location. This was the case with the rubies decorating a letter made of pure gold that King Alaungpaya of Burma sent to the King of Great Britain, George II, in 1756. The museum where the letter is now held contacted him several years ago, Häger recollects. "They commissioned us to find out where the rubies came from." Although the world's best known ruby mines are in Myanmar, the former Burma, there are also significant deposits in neighboring Thailand. The results of analysis of the inclusions showed that the gemstones on the remarkable Golden Letter had their origin with high probability in Burma.

When conducting investigations of this kind, it is essential to use non-destructive analytical methods. Researchers employ microscopy and spectroscopic techniques. Raman spectroscopy has become of considerable relevance, Häger adds, because it allows for the examination of inclusions without damaging the stones. These inclusions provide information for dating the stones and identifying their origin. Inclusions can also tell specialists whether the color of a stone has been modified and what technique was used to do so. The treatment of stones is a perfectly legitimate procedure, but it can affect the value of a stone. "You can do what you like as long as you declare what you have done," emphasizes Häger.

"We can find evidence of anything"

Another important field in gem materials research is the identification of synthetic stones, lab-made counterparts of the minerals. Even expert gemologists are not able to readily distinguish these from genuine gemstones. "There are very good synthesis techniques now available, and it is difficult to detect when these have been used," concedes Häger, only to add: "But we can find evidence of anything. It is only a question of putting in the necessary effort." In the last years, synthetic techniques have improved especially in the diamond sector. In fact, it is already possible to make large lab-grown diamonds at a fraction of the cost of mined stones.

This is not only of interest to the jewelry sector but also to manufacturing industry, in which diamonds are used, among other things, in tools because of their unique properties. And the specialists in Mainz are also in demand in this connection. "I was contacted recently by a company that had discovered that certain synthetic diamonds exhibited behavior different to that of natural stones in their tools. They were looking for an explanation,” reports Häger. And he was able to answer their questions.

Häger himself is very enthusiastic about yet another aspect of gemstone research, namely the color enhancement and modification of gemstones. "The effects of temperature treatment is an intriguing research field I'm very much interested in," he concludes. "I just don't have the time – yet."

Text / Translation: Alexandra Rehn / JGU